- Home

- Mark Hansom

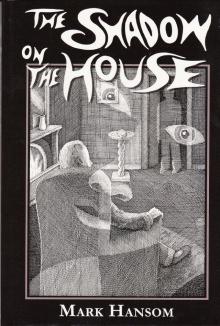

The Shadow on the House

The Shadow on the House Read online

THE SHADOW

ON THE HOUSE

Mark Hansom

Ramble house

The Shadow on the House by Mark Hansom

Introduction © 2009 by John Pelan

Cover Art: Gavin L. O’Keefe

Preparation: Fender Tucker

Dancing TuatAra Press #3

The Shadow on the House

Introduction by John Pelan

Welcome to one of the finest novels of psychological horror of the last century . . . That this novel is being reprinted should surprise no one. That a masterpiece of this calibre should have remained out-of-print and known only to the cognoscenti of the horror genre for seventy-five years is more than a little puzzling. Perhaps the most surprising element of all is that this book was the debut novel of a gentleman who went on to author several novels of equal merit and then after four years, seven novels, and one short story vanished as suddenly as he had appeared.

To present a convincing portrait of the darkest and most aberrant workings of the human mind is a difficult feat. In this arena Mark Hansom can stand as a peer with the likes of Peter Straub, Robert Bloch, and Ramsey Campbell. All of the above have offered up seminal works of psychological horror wherein the reader almost expects to find a supernatural agency at work. Writing a novel that relies on the perspective of a protagonist who may or may not be not be wholly reliable isn’t an easy feat to pull off. Relevant details must still be conveyed to the reader and even if the protagonist is mad as a hatter, the standard conventions of the horror mystery novel still need to be adhered to. In other words, while his perspective of other people may be skewed by his insanity, descriptions of their actions as relevant to the story must be scrupulously described so as to not “cheat” the reader.

Bloch gave us Psycho after two decades of writing short stories of both supernatural and non-supernatural horror. Ramsey Campbell spent a long apprenticeship writing pastiches of H.P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos stories before offering up such masterpieces as The Face that Must Die and The Doll Who Ate His Mother. Peter Straub began his career as a gifted poet, progressed to novels and short stories and had a substantial body of work behind him by the time he launched the remarkable series of “Tim Underhill” stories that includes Koko, The Throat and several other pieces.

Mark Hansom submitted his credentials to join this august company with his very first work of fiction. The Shadow on the House would be an impressive book under any circumstances. The characters are fully realized (even if everyone isn’t exactly who or what they seem to be); the plot moves along briskly with no wasted scenes and as the oppressive sense of impending doom grows stronger the astute reader is able to piece together the clues that have been presented throughout the story and come to certain conclusions about the main characters just as the author pulls the curtain aside and reveals all.

The Shadow on the House has the distinction of being Hansom’s only novel that was published in the US as well as the UK during his lifetime (in 2002, Midnight House published a new edition of The Beasts of Brahm, which is still available from the publisher. E-mail [email protected] for details. Ramble House customers may purchase the book for the discount rate of $35.00 post-paid simply by saying “Fender sent me” in their e-mail). The Shadow on the House was also cited by the late Karl Edward Wagner as one of the thirty-nine best horror novels of all time. However, it is the opinion of this writer that at least two of his later novels were even superior. Mr. Wagner did confide to me that at the time his article and list appeared, he had read no other Hansom novels; so it’s quite possible that had his article appeared a few years later Hansom may well have been represented with a couple of additional entries.

So who was this mysterious author whose star burned brightly for such a short time? The fact of the matter is that no one really knows for certain . . . Even though I was responsible for his entry in the encyclopaedia Supernatural Literature of the World, I was unable to include more than a brief bibliography and some conjectures as to what may have become of him . . . We do know that “Mark Hansom” was a pseudonym; there are no records of a person with that name being born (or dying) in the United Kingdom that could possibly have been the author. The man writing as Mark Hansom began his literary career in 1934 and his activity seemingly ended almost to the day that Great Britain entered the Second World War. Assuming that he was a young man in mid-to-late twenties at the time it’s not at all unreasonable to think that he may have died in the service of his country. A colleague of mine proposed two theories as to his identity, the first is almost too absurd to comment on; namely, that “Mark Hansom” was yet another pseudonym of Charles Cannell (the author better known as “E. Charles Vivian” and “Jack Mann”). What makes this theory easy to refute is the great disparity in styles between the two authors. Some of the indicators are the class-consciousness of Hansom; which implies a first-hand familiarity with the aristocracy and is a distinction completely ignored by Cannell. Secondly, anyone that has read Cannell under any of his by-lines will immediately see his fascination with aviation. One recurring motif in Cannell’s work is that if airplane travel is involved, one is assured of a lengthy description of the plane, the mechanics thereof and possibly even the history of that particular model. If Hansom needs to use an airplane to move his characters from one place to another, we get no such descriptions; the airplane is merely a device to get the characters from point A to point B. Most definitely not the same person.

This same colleague also suggested that the obviously pseudonymous “Rex Dark” might also be Hansom. Other than the sheer illogic of using two different pen-names to sell the same sort of books (thrillers) for the same imprint, there’s also the fact that “Rex Dark” was big on recurring characters and while Hansom used a recurring theme (killing off the villain early in the book only to have him return from the grave to wreak further havoc), he did not re-use his characters even though the opportunity presented itself. Lastly, and most importantly, I’ll bring up that issue of class-consciousness once again. This is important as both a stylistic clue and very probably a clue to Hansom’s identity. Mark Hansom writes of the upper classes and the unwritten rules governing the servants with the authority of someone writing from personal experience. There are indications that the man writing as “Mark Hansom” was of the upper rather than the lower classes.

One bit of circumstantial evidence is the fact that in the pre-WWII days, the publishing industry was still considered suitable employment for a gentleman, who while wealthy enough to not need to work was nevertheless encouraged to get a taste of the business world by working for a few years. An example would be Sir Charles Birkin, who served his apprenticeship in the business world as an editor for Philip Allan and as a result, brought out the justly famous “Creeps” series. The hint that Hansom may have worked in publishing is based on a rather odd set of circumstances . . . Some few years after their initial publication, Mellifont Press reissued all of his books, the last in 1951. What makes this a bit unusual is that Mellifont was a reprint house and while they did indeed publish a number of thrillers originally from Wright & Brown (including a few titles by “Rex Dark”), two of their selections by Mark Hansom were issued in abridged format. As it really isn’t cost-effective to order up a re-write in such circumstances, one has to wonder if there was authorial involvement and if perhaps “Mark Hansom” was connected in some way to Mellifont Press? It could just as easily be that another employee of Wright & Brown made the move to Mellifont and recalled both Hansom and Dark as being among their more consistent sellers. The most unusual fact is the reprinting of Master of Souls in 1951, a full fourteen years after its initial publication. Generally speaking, Mellifont tried to get their reprints out wit

hin five years of a book’s initial release in order to capitalize on any publicity the book had garnered (much as mass-market publishers do today). Publishing a paperback fourteen years after the hardcover just simply isn’t done unless there’s an editor really pushing the book.

So, this leaves us with two possible scenarios as to the fate of the man writing as “Mark Hansom”. One of the many who died serving their country in WWII, or a life spent in the publishing business, perhaps affected so much by the horrors of war that he lost interest in the lesser horrors of the supernatural tale . . .

What we do know for certain is that he did leave a legacy of seven very fine novels a great novelette, and that at least five of these will see publication from Dancing Tuatara Press.

John Pelan

Midnight House

Summer Solstice 2009

THE SHADOW

ON THE HOUSE

CHAPTER I

Sylvia Vernon

I

am — or was — the least superstitious of men; and when I managed to secure a place at Lady Somerton’s dinner-table I thought I was doing merely a tremendously clever thing, in the manner of a young man who has not yet begun to take life seriously and who can find pleasure in bravado for bravado’s sake.

There was nothing more in it than that. I thought what a grand thing it would be to be present at one of Lady Somerton’s dinners — which were celebrated among those who set store by such vanities — and I managed to secure an invitation through the kindness of young Christopher Knight. I had no suspicion that the innocent matter of eating a dinner — even one of Lady Somerton’s celebrated dinners — was to be more than a normal evening’s entertainment; and I dressed with my usual care and set out in a taxi from my rooms in Brompton Road, arriving at Lady Somerton’s Park Lane residence within a very few minutes,

It was a cold evening in October. The Park, immediately beyond the railings, was aglitter with the flashing lights of hurrying cars; but behind these lights — away under the trees — was mysterious darkness. It struck me then that we know very little of the world about us, for the darkness and mystery of the silent distance moved me to reflect upon the manner in which shadows affect us, and to wonder at the sinister atmosphere of trees brooding in the night.

But I soon dismissed these thoughts. Life to me then was an inconsequent affair of pleasure. I saw only lightness and gaiety, and deliberately hid my head in the sand to things of a morbid nature.

To that end I remember wondering how young Christopher managed to have the entree to Lady Somerton’s, for the residence in Park Lane was not open to everybody, and Christopher, like me, was quite undistinguished in the world. And from that question, which was soon to be explained, I turned to speculation on the manner in which he had secured an invitation for me and, laughing to myself, wondered what sort of reputation I should be expected to maintain.

Christopher had not arrived when I was shown into the drawing-room. Lady Somerton was there, and, there were also present half a dozen elderly people who were probably distinguished but who, like all the distinguished people I have ever met, looked quite ordinary. And Sylvia was there.

I call her Sylvia now. But when I entered that drawing-room I had never set eyes upon her and had no anticipation of the profound emotional upheaval that was about to take place within me.

I saw a girl of the most unspeakable loveliness, and for the first moment of my setting eyes upon her I am afraid that I simply lost my normal self-restraint and stared at her, incredible. Perhaps I exaggerate. No one present seemed to be aware of my condition, and introductions were performed as though this divinely beautiful creature were any ordinary girl in any ordinary drawing-room, and as though I had not, in a moment, suffered a complete revolution of all my ideas of beauty, and as though life henceforth would not be a totally different thing for me.

I felt all these things, as I say. And I felt, also, that they showed in my manner.

But one thing I did not feel — the beginnings of tragedy. That seems a strange remark to make at this point in the narrative; but I have, since my first meeting with Sylvia, come to associate such beauty as hers with tragedy of the most terrifying kind.

I faced the introduction to Miss Vernon — Sylvia Vernon was her name — with what carelessness I could command. Fortunately she was one of the most unaffected girls I have ever met, and her friendly manner did all that could be done towards putting me at my ease. Had she cared to try to put me out of countenance by adopting a distant air I should have been quite thrown into confusion; but Miss Vernon was perfectly natural and I found myself conversing with her in a manner that surprised me after my utter bewilderment on first seeing her.

Lady Somerton, who had one of the most wonderful complexions I have ever seen, and whose expression always became delightfully animated when she spoke, left Miss Vernon and me together and hurried off to attend to some other of her guests.

“My aunt has been good enough to take me in hand,” Miss Vernon told me when, with the precipitancy of youth, we had reached a personal footing in the way of conversation.

“Lady Somerton is your aunt?” I asked.

We had drawn aside, the two of us. We were the only young people present, and the other guests — three ladies and three gentlemen — were engaged with the hostess.

But though we had thus quickly arrived at a stage of pleasant familiarity, I was not the less affected by her amazing loveliness. She had been given a name and she had been given a voice and she had exchanged commonplaces with me and had even laughed at some happy remark of mine; but still she retained in the fullest measure that aura of impersonal beauty with which I had invested her. Her fair hair, her blue, sincere eyes, her slim dignity — these, in Miss Vernon, were mysteries that I could not understand. All that I could understand was that I had been translated into a higher sphere of emotional existence.

In short, I was hopelessly in love.

Lady Somerton now joined us. For this, strangely enough, I was grateful. No words of any importance had been exchanged between Sylvia Vernon and me (How could they, on such short acquaintance?), but I was afraid that my feelings must show through my banal conversation, and I was glad to be relieved by our hostess.

But of one thing I was certain: I should never rest happily until I had made Sylvia Vernon my wife.

A wild observation to make in the circumstances! A wild observation for even a very young man to make! But I made it, and I made it in all seriousness. That I had known her for less than ten minutes was a factor of no importance. That she was of a social status far above mine was likewise a factor of no importance. She had claimed absolute dominion over me. Nothing else mattered.

Then Christopher was announced.

At the mention of his name Sylvia looked up quickly towards the door and took an involuntary step forward, her eyes lighting up with a smile.

Lady Somerton went forward to welcome Christopher, and I was again left alone with Sylvia.

But now she was a different Sylvia. She was looking across the room, interestedly, expectantly, waiting for Lady Somerton to be finished with Christopher. Her lips were parted in a half smile. She was taking not the slightest notice of me.

I knew then how it was that Christopher — the undistinguished Christopher — had the entrance to Lady Somerton’s mansion. And I knew what it was to be jealous.

Christopher came towards us, embracing both in his smile of greeting. But his eyes were devouring Sylvia almost all the time, and she accepted his admiration happily and returned it in full measure.

I joined in the conversation; but I had to force myself to act as though I enjoyed the position. And all the time I was telling myself not to be a boor, to congratulate Christopher — if only in my heart — for having succeeded so well as to win the love of such a singularly beautiful girl. But I could not force myself even to acknowledge that he had won Sylvia’s love. She had taken me off my feet to such purpose that I could not contemplate her belonging

to anyone else — even her belonging to dear honest Christopher who, as I should normally have admitted, was worthy of the finest girl in London.

“Mr. Strange has been telling me,” said Sylvia, “that you and he are called ‘the inseparables’ at your club. It isn’t at all nice of your friends to give you nicknames. I don’t like nicknames. When they mean anything at all they are usually over-candid and seldom flattering. But what I want to remark is that if you are such good friends why is it that I haven’t met Mr. Strange before this evening?”

“Easily explained!” said Christopher, running his hand over his fair curly hair. “There used to be a music-hall song (Of course, you haven’t heard it!) which advised one never to introduce one’s sweetheart to a pal. You should really ask why you are being allowed to meet Martin even now. I’m afraid I’m being guilty of folly in running against music-hall wisdom. For wisdom is to be found in the most unlikely places, you know.”

It was then that we were summoned to dinner, and Christopher’s remarks were immediately forgotten, I suppose, by both him and Sylvia. But they remained in my mind, for I could take them seriously.

Ten of us sat down to dinner. I was placed between a lady in black, who had a son in India, and a lady in pale blue, who had no son at all but who had five daughters; and the first three courses were spent in listening to these two — one of whom would have given the world to have her son back on her hands, while the other, so far as I could gather, would have given the world to have her daughters off hers.

Then someone — a Professor Wetherhouse, with whom I was to become more closely acquainted in the future — began on the subject of ghosts.

The Shadow on the House

The Shadow on the House