- Home

- Mark Hansom

The Shadow on the House Page 8

The Shadow on the House Read online

Page 8

I could see that he was looking at me out of the corner of his eye, and that made me uncomfortable. I wondered whether I had handled the situation so awkwardly as to make him suspect that I had never once thought about the inquest. But that, I argued, was impossible.

Yet, as we walked along the path towards Park Lane — at a gentle pace, for the Professor was past the violently active part of his life — he continued to look at me, as I thought, stealthily, from time to time.

“The worst of it is,” he remarked, “that there isn’t the unanimity that one hopes for in a case of this sort. The verdict is plain enough, of course — misadventure. But — ”

I was relieved to hear that the verdict was in accordance with my expectations. I could now talk more freely to the Professor.

“But,” he went on, “when you read between the lines you see that there was some doubt in the mind of the court. But you were there, of course, and you had a better chance of forming an opinion than I who only saw the report in the newspaper. What did you think?”

“I wasn’t there,” I said, with an effort at frankness, though conscious again of his sidelong, stealthy glance. “I couldn’t face the ordeal. I’ve known Mick since he was a boy. That might seem to you, sir, to be all the more reason why I should be present on such an occasion. But the reverse is the case. I couldn’t face it.”

I was surprised at the ease with which I told that lie. It was a small matter. It was no business of the Professor’s whether I was at the inquest or not. I might quite readily have told him that I had no particular love for my cousin in life and that I was not one to indulge in spurious sentimentality because my cousin was no longer alive. But I dissembled. Something made me wish to hide the truth.

The Professor seemed to swallow my excuse.

“True, true!” he said. “I understand. It is all very distressing . . . I wondered whether you were in agreement with the verdict.”

“Oh, yes!” I said. “I can’t see what other verdict they could have brought in.”

We walked on for a minute or two in silence.

I was wondering, if the truth is to be told, just why the Professor had thought of coming over to see me this morning. He had said that he had set out to call on me for the purpose of offering his sympathy, and I suppose I ought not to have doubted his word. But it seemed strange to me that such a busy man as he should be willing to spare time from his university duties in order to visit me personally when a short note would have served his purpose equally well. I had seen him only about three times in my life, and I had no reason to believe — though he was the kindest of men — that he was moved by any particularly strong feelings for me. I say nothing, I hope, that will give the impression that the Professor was lacking in kindliness of heart — for he had that in an unusual measure. What I would say is merely that my case did not seem to merit so much solicitude.

“As I told you,” he said at last, “the court seemed to be in some doubt. They gave the ‘misadventure’ verdict, it would seem, because it was the — the most charitable verdict. You knew him very well. You don’t know of any circumstances in his life that might make it possible to doubt the verdict?”

“No,” I replied. “And really I did not know him so very well. Until he appeared a few days ago I had not seen him for years — two years at least.”

“Oh!” he said. “I understood that you two were rather intimate friends. Though it’s not usual for cousins to be intimate friends, when you come to think it over. You weren’t enemies, I hope?”

“No,” I assured him, hastily, whole-heartedly.

This cross-questioning, even from the Professor, was slightly distasteful to me. I had a terrible secret — shared only by the faithful Makepeace — to keep, and I must never allow anyone to suspect even that I had a secret, let alone to suspect that that secret had anything to do with my cousin’s death. Therefore I was eager to assure him that there never had been the least bit of ill-feeling between Mick and me.

“It’s more usual,” he said, with a vestige of a smile, “for cousins to be enemies than to be friends — especially in the case of two brought up together, as I understand you two were. Brothers must have a certain feeling of loyalty towards each other and towards their own branch of the family. Friends are friends in spite of everything else. They are not influenced by family affairs. But cousins — the friendship of cousins is made difficult at every turn. They can’t ignore each other as friends who quarrel can, and the loyalty of each to his own branch of the family makes for disputes rather than for peace.”

The Professor, with his rather tall figure and his white beard, looked and spoke very like a typical professor just then; and I sauntered along beside him wondering whether he were talking merely for the sake of talking or whether there were some design behind this call upon me and the remarks that had followed.

I assured him again that such relations as there had been between Mick and me had been of the very friendliest.

Soon after that he left me. We came to a point where the path was crossed by another, and here the Professor stopped.

“You’ll excuse me if I leave you now,” he said. “I am due to give a lecture in half an hour’s time. Give my regards to Sylvia, won’t you!”

He did not shake hands, but merely flourished his walking-stick in adieu and set off at a moderately brisk pace.

But he had not gone many steps when he stopped and came back. His hail arrested me as I, too, set off towards my destination.

“Have you heard,” he said, when he had come quite close to me, “have you heard that the police are on the track of a man in connection with the murder of young Knight?”

I stared at him. He must have thought me slow of comprehension, but for a moment I was totally incapable of replying. Panic almost got the better of me. I felt myself to be in the midst of a web of circumstances wherein fact and fantasy, truth and misunderstanding were all so inextricably mixed that no one could say which was which — no one except Makepeace and me, and we dared not speak. The police were on the track of a man in connection with the murder of young Knight! They were on the track of an innocent man — for it was not a human being who had done that deed — and the innocent man might not be able to prove his innocence.

Would there be no end to the tragic effects of my unwitting invoking of that mysterious force!

“Oh?” I managed to say at length. “Do they think they’ll catch him?”

“That I can’t tell,” he said. “But don’t mention it to a soul. It has not been made public, only I happened to hear something, and I am telling you because you and he were such friends, and you, naturally, ought to know what is going on.”

And before I could reply to that — before I could ask who the man was and for what reason the police suspected him — the Professor had bidden me a final good-bye and had gone.

Then it struck me that he had not remarked on the fact — so outstanding to me, and which I thought everyone must notice — that it was unusual for two separate violent deaths to occur among the friends of one man.

CHAPTER X

Mr. Ashton

T

hree months passed. And three months is a long time in the life of a man in his early twenties. Even the unspeakable fears that had taken possession of me when it was proved beyond question that I was being watched over by a conscious, shadowy, and undoubtedly sinister presence could not maintain their intensity before the healing influence of three whole months. Time, youth, health, and the will not to dwell on morbid matters had brought me back almost to my usual light-heartedness.

And I had had much to do. The legal affairs in connection with the estate occupied me for a considerable time. And as I was now one of the wealthiest young bachelors in London I found that I had a great many more friends than I should ever have believed I had; and these friends seemed to make it their one business in life to see that I was never at a loss for some sort of entertainment. Even Professor Wetherhouse seemed to h

ave become particularly attached to me, but that I put down to some natural liking on his part, for it was inconceivable that my fortune played any part in his having chosen me as one of his intimate friends.

Yet I was to have my suspicions about the Professor.

Only Sylvia remained the same. She was totally unaffected by my having inherited so much wealth. Perhaps she was thinking of the terrifying suspicions that had come to her when my cousin died, and was living on the borderland of fear. I could not tell, because I had kept discreetly silent on the subject when with her, knowing that time would cure her of the foolish superstitious belief that her lovers were destined to come to tragic ends.

I had given up my little place in Brompton Road and had, for the time being, taken a furnished flat in Grosvenor Square. Sylvia and I were to be married before the summer was out, and it was my intention to open up Bolton Towers again — which had remained closed for years, for Mick had had no interest in the place — and to take a Town house, and generally to live like a gentleman who knew what he was about.

I was discussing these matters with Sylvia one warm afternoon. We were alone by the open window of the drawing-room that looked out on to Park Lane lying beyond our precious patch of garden — for patches of garden are precious in Park Lane, costing I don’t know how many pounds a square foot.

To me this was an occasion of almost inconceivable happiness. To be discussing plans for a future that embraced Sylvia and me as man and wife was to indulge in one of the highest delights of a thinking being — the delight of anticipation.

“And you and Lady Somerton will come down with me one day soon,” I said, “and look over the place. And you will choose your own rooms. That will be a more difficult business than it sounds, for the place has been added to from time to time and it isn’t easy to tell which are the principal rooms and which aren’t. And the view from all sides is equally good, so that won’t help you in your choice . . . And then there will be decorations to be thought of. You’ll probably want to modernize some of the interiors . . . Oh, we’ll have a splendid time!”

Sylvia smiled at that, but not so enthusiastically as I could have wished. I remember thinking, then, that perhaps I was putting a greater value on Bolton Towers than it merited. That, if it were so, was excusable, for I had lately realized how worrying would have been my position had I not inherited the estates and had I been compelled to try to make a show in life on about fifteen hundred a year. Or it might be that Sylvia, having been used to grandeur all her life, took grandeur as a matter of course, and could not work up a great deal of enthusiasm over even one of the stateliest of the stately homes of England.

“Do you think it will be necessary for us to go down beforehand?” she asked.

At that my face fell; but she added hurriedly, and with, I thought, a slight perturbation:

“I mean, wouldn’t you rather that I left all that to you? It will be more delightful for me to go to the place for the first time after we are married. To go before will take all the novelty off the experience.”

All of which I thought was rather excessive straining upon a weak excuse for not visiting Bolton Towers.

Her lack of enthusiasm had struck me, and now this unconvincing excuse struck me, and for the moment I wished that she were less beautiful, less mysteriously feminine, more easily affected, of commoner clay so that she might take more pleasure in the simple things of life. But when I looked at her as she turned her head for an instant to let her eyes roam over the golden pendants of a laburnum tree that grew close to the window, I knew that it was her distant, mysterious loveliness that had first attracted me and that I should always be content to worship without understanding or trying to understand.

I never thought to ask myself whether she loved me as much as I believed she did.

“And, in any case,” she went on, turning from her contemplation of the laburnum tassels and fixing her gaze not on my eyes but on my necktie, “I should hate to disturb the decorations of such an old place. The charm of such a place as Bolton Towers lies in its being undisturbed from one generation to another. Don’t you think so?”

I agreed on this comparatively minor point, though I might quite truthfully have said that I should be perfectly happy for her to take it into her head to have the entire place rebuilt.

I should have been almost glad if she were to exhibit some such piece of extravagant vanity, for I was disappointed in the calm manner in which she had accepted my suggestions.

Then I recollected that the only times on which she had shown any really glowing enthusiasm was when Christopher Knight entered the room on the evening of my introduction to her, and when she met Mick and me in the Park and took us back to lunch.

These two — Christopher and my cousin — seemed to have had the power to awaken what girlishness lay behind that mysterious reserve of hers. I had not been able to awaken it.

Yet I did not try to analyse that matter. I was too much of the worshipper to question her moods. It was sufficient for me that she was going to be my wife.

At that moment Lady Somerton came into the room, and looking about her and seeing us there she advanced towards us, her face lighting up into its usual animation.

Tea, she said, was waiting in the little drawing-room downstairs; and she took my arm as she spoke.

Sylvia preceded us out of the room and down the staircase; and at the half-landing I caught a glimpse of Lady Somerton’s face. For that fraction of a second the animation had gone and she was looking at Sylvia, who was beginning to descend the second flight, with an expression half-questioning, half-annoyed. Almost at once she turned to me and continued her chatter about something or another — I forget what. But I had seen that glance of disapproval, and my loyalty towards my goddess sprang up within me.

I almost wished that Lady Somerton, who still had my arm, would openly remonstrate with Sylvia upon her lack of brightness — for that I took to be the reason for the disapproving glance at the bend of the staircase — so that I might have a chance of defending Sylvia and pointing out that there were qualities more desirable than effervescence of spirits.

Of course, no such chance presented itself, and I certainly could not have taken advantage of it if it had.

The Professor was in the little drawing-room, and he was talking confidentially with someone whom I had never seen before. They drew apart as we entered, and I had time to observe that the stranger was a middle-aged man of sturdy build whom I took to belong to one of the professions.

The stranger was introduced to me as Mr. Ashton, without any qualifying particulars. And over tea he continued to be referred to — when he was referred to, which was not often — as Mr. Ashton; and no hint was dropped regarding what particular Mr. Ashton he might be, or what his profession might be, or why he was present in the little drawing-room.

Mr. Ashton himself spoke little. I doubt whether he said three words during all the time that we spent over tea. This fact was very noticeable because at Lady Somerton’s the people one met were invariably well-known people, and a newcomer was encouraged to talk. Most of them, I might say, did not require encouragement.

It was after tea that the Professor took me aside.

“You were telling me the other day,” said the Professor, “that you would soon have to be on the look-out for a male secretary. Now that money has made your life so much more complicated, as you were saying, I suppose a secretary is a necessity. To most of us such a person is a luxury. But that’s beside the point. I want to ask you whether you would care to take Ashton for the job. He is a man I used to know very well. But I understand that life has not been too good to him, and I thought — ”

So that was the reason for the appearance of the uncommunicative Mr. Ashton! It was rather an unusual method, I thought, of introducing a prospective employee to a prospective employer; but it had this peculiar feature about it, namely, that I could not possibly refuse to accept Mr. Ashton there and then to fill the post.

&nb

sp; I did accept him. I accepted him without asking for any particulars regarding his abilities, without asking for any particulars whatsoever. The fact that the Professor had recommended him answered everything favourably before it was asked.

Later I had a quiet, formal talk with Mr. Ashton himself.

I had expected him to be a cultured man, of course; and in that I was not disappointed. But I remember thinking it queer that life had not been too good to him — an expression of the Professor’s signifying, in the circumstances, that Ashton couldn’t find work. It seemed queer because of the fact that Ashton’s manner was that of a man who has a calm and easy confidence in himself, and who has not had his spirit cowed by a series of defeats. His personality was forceful, albeit he said little. And though he called me sir after almost every phrase, I had the feeling that he was my superior in every way and, moreover, that he was perfectly well aware of the fact.

In short, he made me feel something of an upstart, and made me almost ashamed of the accident of birth that had put me in the rôle of master and him in the rôle of servant.

Had I been free to choose I should have chosen a younger man for my secretary — one to whom I could state a command without having the feeling that I was begging a favour. But the Professor had caught me on the hop — not, did I think, intentionally — and I could do nothing but take Mr. Ashton into my service, hoping, no doubt, to acquire a commanding dignity in time.

And, all that being settled, the Professor and Mr. Ashton left together.

They had barely been gone five minutes, and Lady Somerton was only just beginning to interest me with an account of a social function that she had attended on the previous day, when a maid came in to announce Mr. Wetherhouse.

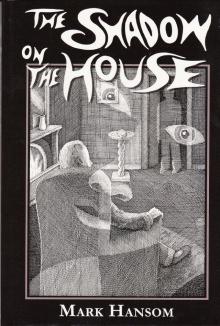

The Shadow on the House

The Shadow on the House